Image credit: Unsplash

In an ongoing court battle, the chief executive officers of both Kroger and Albertsons responded to questions from the federal government on Wednesday that the companies’ merger would allow the two grocery stores to lower prices while enabling them to compete more effectively with retail giants like Walmart, Costco, and Amazon.

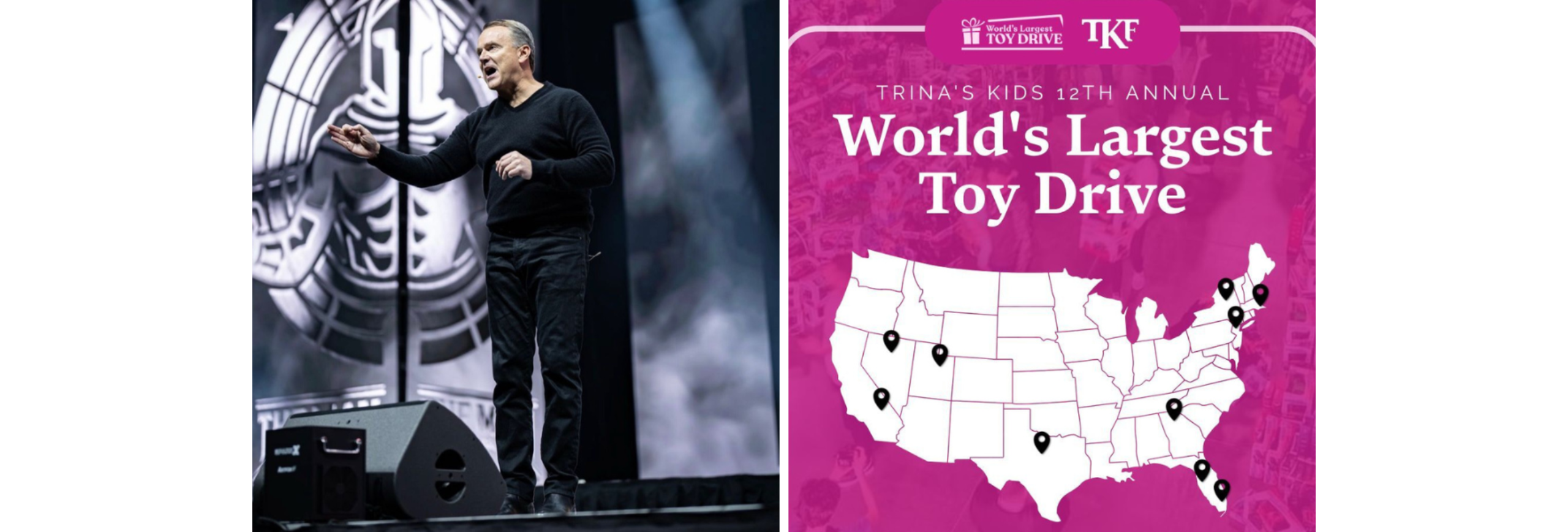

Appearing in Oregon’s U.S. District Court to testify against the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) attempt to block the merger, Kroger CEO Rodney McMullen stated while under questioning by a lawyer representing his company, “The day that we merge is the day that we begin lowering prices.”

Combining Kroger and Albertsons would mark the largest supermarket merger in U.S. history. Proposed in October of 2022, Kroger agreed to purchase Albertsons; however, the FTC sued to prevent the $24.6 billion deal.

The FTC argues that the merger would hurt competition in certain areas where the two are each other’s primary rivals, ultimately eliminating competition and leading to higher food prices for customers who are already struggling to provide.

According to company documents referred to by the FTC lawyers on Wednesday, Kroger and Albertsons are primary rivals in multiple regions, including southern California and the Portland metropolitan area. However, a Kroger attorney countered, stating that superstore giant Walmart remains the company’s largest competitor in a majority of markets across the country.

McMullen shared that Albertsons’ pricing is 10 percent to 12 percent higher than his company, and the merged companies would try to reduce the disparity as part of a strategy to retain customers. Right now, Walmart controls around 22% of all U.S. grocery sales, and the combined efforts of Kroger and Albertsons would lead to a 13% control of grocery sales.

Albertsons CEO Vivek Sankaran argued that the merger would help boost growth, supporting store and union jobs, because many of its and Kroger’s competitors have few unionized workers, like Walmart. Yet, when Sankaran was asked what Albertsons would do if the merger did not go through, the CEO stated that he might pursue “structural changes” like laying off employees, closing stores, and exiting certain markets, particularly if unable to find alternative ways to lower costs.

“I would have to consider that,” he said. “It’s a dramatically different picture with the merger than without it.”

However, an FTC lawyer highlighted a written statement provided by Sankaran to the U.S. Senate in 2022 when testifying about the merger, where he said his company was “in excellent financial condition.” Sankaran countered by pointing out the changes in the economic landscape and certain conditions.

McMullen addressed the closing-stores issue that has shoppers worried in areas where both Albertsons and Kroger operated stores, stating that Kroger was committed to not closing any branches immediately if the merger is finalized; however, it might go down that road if it decides location changes or consolidations are needed.

For the three-week hearing, which has reached its midpoint, the testimonies of both McMullen and Sankaran are expected to be critical components. What the two CEOs say under oath about prices, potential store closures, and the impact on workers is likely to be scrutinized in the years ahead should the merger go through.

Based in Cincinnati, Ohio, Kroger currently operates 2,800 stores in 25 states, including brands like Ralphs, Smith’s, and Harris Teeter. Albertsons, based in Boise, Idaho, currently operates 2,273 stores across 24 states, which includes brands like Safeway, Jewel Osco, and Shaw’s. Combined, the two companies employ around 710,000 employees.

Should the proposed merger go through, Kroger and Albertsons would sell 579 stores in places where their locations overlap to C&S Wholesale Grocers, a New Hampshire-based supplier to independent supermarkets that also owns the Grand Union and Piggly Wiggly store brands.